Biblical Scholarship: A Critical Look at the Oldest and Most Well-Known Manuscripts

Bible scholarship of the past 150 years has placed much attention on a very small number of manuscripts. While there are over 5000 known New Testament manuscripts, attention has been placed on less than ten. Of these, Codex Sinaiticus and Codex Vaticanus have been exalted as the “oldest and best” manuscripts. The oldest claim has been disproved elsewhere. This document will focus on the nature of these two favored manuscripts.

Sinaiticus has been recently made available to all on the internet by the Codex Sinaiticus Project, with the mainstream media and general Christians fawning over this “world’s oldest Bible.” This manuscript, in conjunction with Codex Vaticanus, form the basis for most modern Bible translations. However, these two manuscripts differ substantially from the text of the bulk of the manuscripts. Thus, the public needs to know the truth about these manuscripts.

Contrary to what has been taught in most seminaries, these two manuscripts are worthless, and hopelessly corrupt. Dean John Burgon, a highly respected Bible scholar of the mid to late 1800’s, wrote of these manuscripts, “The impurity of the Texts exhibited by Codices B and Aleph [Vaticanus and Sinaiticus] is not a matter of opinion but a matter of fact.” These documents are both of dubious origin. It has been speculated by some scholars that one or both were produced by Eusebius of Caesarea on orders of Emperor Constantine. If this is true, then these manuscripts are linked to Eusebius’s teacher Origen of Alexandria, both known for interpreting Scripture allegorically as opposed to literally.

Vaticanus is the sole property of the Vatican; it has been a part of the Vatican library since at least 1475. Its history prior to that is unknown. It was written by three scribes, and has been corrected by at least two more. Vaticanus adds to the Old Testament the apocryphal books of Baruch, Wisdom, Ecclesiasticus, Judith, Tobit, and the Epistle of Jeremiah. Dean Burgon describes the poor workmanship of Vaticanus:

Codex B [Vaticanus] comes to us without a history: without recommendation of any kind, except that of its antiquity. It bears traces of careless transcription in every page. The mistakes which the original transcriber made are of perpetual recurrence.

The New Westminster Dictionary of the Bible concurs, “It should be noted, however, that there is no prominent Biblical MS. in which there occur such gross cases of misspelling, faulty grammar, and omission, as in B [Vaticanus].” Vaticanus omits Mark 16:9-20, yet there is a significant blank space here for these verses. Sinaiticus also lacks these verses, but has a blank space for them.

The Sinaiticus was discovered by Constantine Tischendorf in the Greek Orthodox Monastery of St. Catherine, on the Sinai peninsula. Monasteries are known for exceptional libraries, and scholars would often visit to conduct research. St. Catherine’s is no exception. From the monastery’s website:

When Egeria visited the Sinai around the year 380, she wrote approvingly of the way the monks read to her the scriptural accounts concerning the various events that had taken place there. Thus we can speak of manuscripts at Sinai in the fourth century. It is written of Saint John Climacus that, while living as a hermit, he spent much time in prayer and in the copying of books. This is evidence of manuscript production at Sinai in the sixth century.

The library at the Holy Monastery of Sinai is thus the inheritor of texts and traditions that date to the earliest years of a monastic presence in the Sinai.

In earlier times, manuscripts were kept in three different places: in the north wall of the monastery, in the vicinity of the church, and in a central location where the texts were accessible.

This monastery has a library full of old manuscripts. One would then assume that Tischendorf found the prized Sinaiticus one a library shelf, hidden among other manuscripts. Well, this is not exactly the case. He found it in a trash can, waiting to be burnt! Sound incredible? Tischendorf gives his personal testimony:

It was at the foot of Mount Sinai, in the Convent of St. Catherine, that I discovered the pearl of all my researches. In visiting the library of the monastery, in the month of May, 1844, I perceived in the middle of the great hall a large and wide basket full of old parchments; and the librarian, who was a man of information, told me that two heaps of papers like these, mouldered by time, had been already committed to the flames. What was my surprise to find amid this heap of papers a considerable number of sheets of a copy of the Old Testament in Greek, which seemed to me to be one of the most ancient that I had ever seen.

Why would the monks of St. Catherine’s throw out such a valuable manuscript? Perhaps because it was low-quality transcription with heavily corrected text.

Concerning its sloppy penmanship, Burgon writes:

On many occasions, 10, 20, 30, 40 words are dropped through very carelessness.

His colleague Frederick H. Scrivener goes into detail:

Letters and words even whole sentences are frequently written twice over or begun and immediately canceled: while that gross blunder technically known as Homoeoteleuton…whereby a clause is omitted because it happens to end in the same words as the clause preceding occurs no less than 115 times in the New Testament…Tregelles has freely pronounced that “the state of the text as proceeding from the first scribe may be regarded as very rough.”

Sinaiticus has also been corrected by “at least ten revisers between IVth and XIIth centuries.”

No other early manuscript of Christian Bible has been so extensively corrected.

The Codex Sinaiticus Project readily admits:

No other early manuscript has been so extensively corrected.

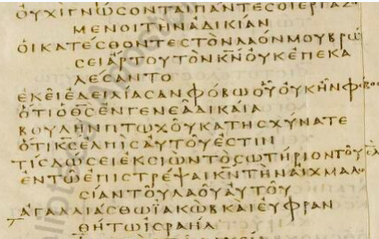

A glance at transcription will show just how common these corrections are.

As you can see from this example (Figure below), it looks like a much-corrected rough draft.

Example

The corrections to Sinaiticus are so numerous that they often overwrite the original text. In many cases, the corrector’s hand is more legible than the original scribe’s. This raises questions about the accuracy of the text and its reliability for translating the Bible.

In addition to the numerous corrections, Sinaiticus also has a significant number of missing pages. The manuscript is incomplete, with many gaps in its text. This makes it difficult to use as a reliable source for biblical scholarship.

It is also worth noting that the Codex Sinaiticus Project has made claims about the manuscript’s “preservation” and “accuracy” without providing any evidence to support these claims. They have also been criticized for their handling of the manuscript and their failure to provide transparency in their methods and materials.

In conclusion, while Sinaiticus is an important and valuable manuscript, it is not without its flaws and limitations. Its poor condition, numerous corrections, and missing pages make it difficult to use as a reliable source for biblical scholarship. Additionally, the Codex Sinaiticus Project’s handling of the manuscript and lack of transparency in their methods and materials have raised concerns about the accuracy and reliability of their work.

It is important for scholars to approach manuscripts like Sinaiticus with a critical eye and to consider multiple sources and perspectives when conducting biblical research. By doing so, we can gain a more accurate understanding of the text and its meaning, and we can avoid relying on a single, flawed source for our conclusions.